I’ve often wondered what it means to practice game design.

When I’m saying to someone: I’m the game designer on the team, what is it that I do?

This might seem a strange question to ask. After all, it’s easy right? You design a game. That makes you a game designer. But then, what is designing a game?

Design process

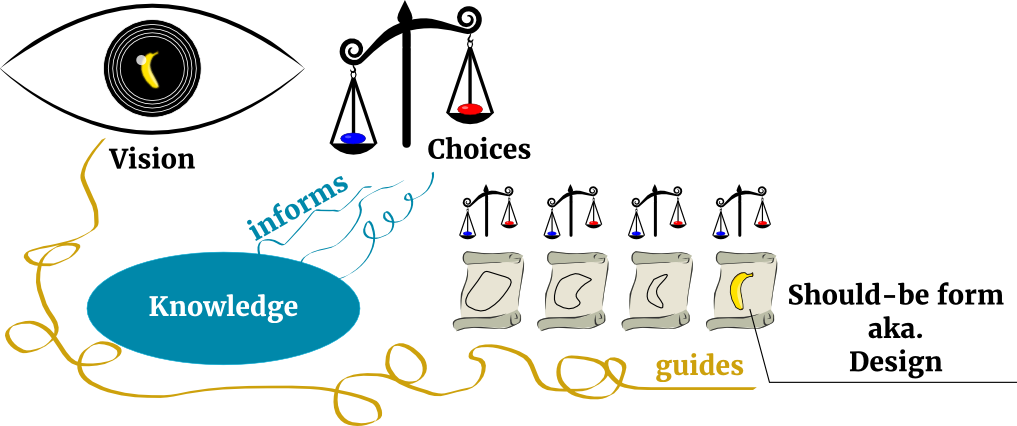

Let’s start by defining designing or the design process. Designing for me is “making informed choices to create a specific ‘should-be’ form for your subject.”

This definition gives a lot of hooks that can be used in your day-to-day design practices.

Let’s go over it.

“making informed choices” Simply put, randomly doing things is not designing. Designing is deliberately choosing one option over another. The metaphorical monkey hitting random keys on a computer will eventually create a videogame. However, this has nothing to do with design, because the monkey is not making choices.

The informed aspect of these choices is actually redundant, because you cannot make a choice when you have no information, because then you wouldn’t be choosing but guessing.

However, the word informed serves as a reminder of exactly that: when you make a choice as part of the design process, you have to make sure you know why you are choosing one option over the other, so you don’t regress to guessing. Of course, this isn’t a binary relationship: there is a spectrum between a complete guess and a completely informed choice. It is impossible to know everything, so naturally any choice will be at least partially a guess. In general, the more you know, the better your choices will be.

Also, this implies that you have to have some knowledge on which you base your decisions. A big part of what you do as a designer is checking whether you have the required knowledge to make certain decisions, and gaining more knowledge if you don’t.

“to create a specific ‘should-be’ form” You have to know what you’re trying to create. A vision or a feeling or a story theme or an insight, or something else. It doesn’t matter, the important part is that you have a clear idea of what you want to reach. It is impossible to design when you have no idea what your endresult should be like. This is because a specific endresult gives your choices a direction, an ultimate criterium that can be used to valuate different options.

so uhhhh… should-be? These words accentuate that you do not actually have to make the thing you’re making to design it. So, in theory (it’s not practical) you can design an entire game without ever making the game itself. It’s not a good idea however, because you do not increase your knowledge of the game you’re making while working on it. (and thus miss out on the opportunity to make more informed choices)

Put differently, this splits the execution, the making of the thing you’re making, from the designing of the thing you’re making.

“for your subject.” Your subject is the thing you’re designing. Your game, your ash tray, your book cover, whatever you are working on. This part is here for completeness, to emphasize that you design something, in our case a game.

What is a game? (and does it matter)

Now that we’ve defined what designing is, let’s define what a game is. Or… not? Recently I read the book ‘Clockwork Game Design’ by Keith Burgun1, in which he outlines four interactive forms2, all of which we call games, but these forms are fundamentally different and have different underlying values.

This opened my eyes to the idea that is not all that useful to try and find an all-encompassing definition of a ‘game’. The thing that helps you most when actually designing a game, is to formulate a clear vision of the kind of game you’re trying to make. Of course, it’s wise to look at existing definitions to formulate this vision, but the practical value of a definition for games in general is small. After all, you’re not designing a game in general, you’re designing a very specific game. This very specific game has specific needs that most likely are not shared by the majority of other games.

By trying to group all different types of games together and finding guidelines to design these, you lose the possibility to find guidelines that work for your specific kind of game.

A different example of this is the book ‘Game Feel’ by Steve Swink3. This book is about a virtual sensation of control when playing games. But, not all games have this. Before going on to say things about this ‘game feel’, the book defines for what kind of games game feel is applicable, meaning in some games there isn’t any game feel whatsoever! By limiting the scope of game feel to a specific subset of games, the author is able to provide much more valuable guidelines for achieving a certain game feel.

So, when you want to improve your game’s design, defining what a game in general is, can be a good first step. However, I believe that in order to find information that is relevant to the games you’re designing, you need to find a more specific term for the kind of game you’re making, and start defining that. (and as more people do this, we’ll have more guidelines that do have value for specific types of games)

This is not to say that there are no valuable insights to be gained from looking at games in general. However, you need to know what to do in a specific situation and for a specific kind of game. For that, you need to have definitions and guidelines for those specific kinds of games.

Sources

Clockwork Game Design by Keith Burgun

1https://www.amazon.com/Clockwork-Game-Design-Keith-Burgun/dp/1138798738

Interactive forms (by Keith Burgun)

2http://keithburgun.net/interactive-forms